EU and the US must forcefully deter further Russian aggression in order to set the development in Europe onto a path where talks, cooperation and economic development can be possible for all writes Gunnar Hökmark, President of Stockholm Freeworld Forum, and Anders Åslund, Senior fellow.

At present, Europe appears to be closer to a big war than at any time since the end of the Cold War. The reason is as evident as when Adolf Hitler started World War II or Joseph Stalin his Winter War with Finland. Vladimir Putin appears to be using the same playbook in his threatening aggression against Ukraine. Whether he will actually assault Ukraine or not is still an open question, but he is making all preparations for a big war with Ukraine.

Russia has now mobilized about 100,000 soldiers to the South, East and North of Ukraine, and American intelligence claims that they are set to increase to 175,000 in January. Ukrainian intelligence has stated that they expect a possible assault in late January or early February. Ukraine has about 250,000 active soldiers and 400,000 war veterans. Russia has much more military equipment, but the Ukrainian soldiers would be far more motivated defending their motherland. A real war would be very bloody. It is also possible that Russia would opt for some kind of hybrid warfare, such as cyberattacks against the Ukrainian grid and banks.

Russia’s Escalation

Russia’s escalation has been as relentless as ruthless. Putin is preoccupied with Ukraine. Since 2008, he has insisted that Ukraine does not exist. In his annual four-hour conversation with Russian journalists on June 30, he claimed that “Ukrainians and Russians are a single people.”

He denigrated President Volodymyr Zelensky. ”Why meet with Zelensky if he has accepted the full external management of his country? The main issues concerning Ukraine’s functioning are not decided in Kiev but in Washington and, partly, in Berlin and Paris. What is there to talk about then?”

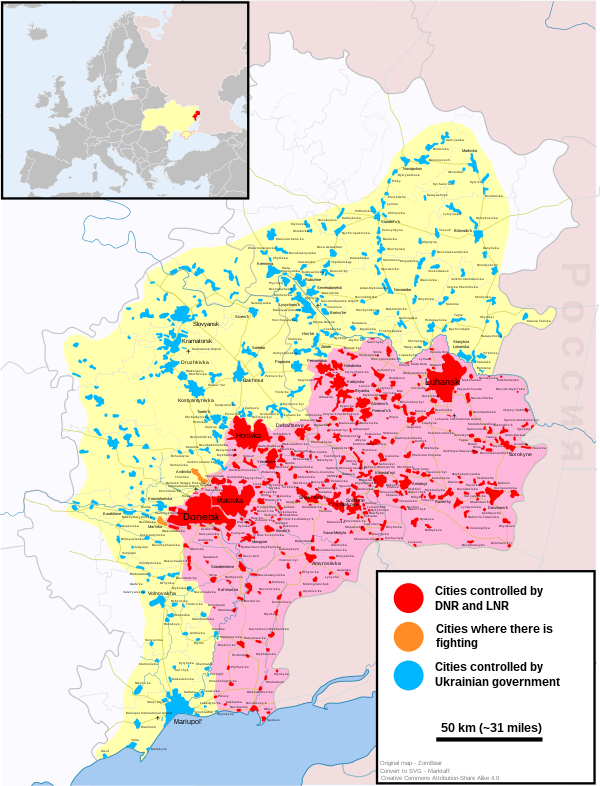

Russia has of course been at war with Ukraine since it annexed Crimea in March 2014 and soon afterwards opened a second front in eastern Ukraine. Some 14,000 Ukrainians have died and hundreds of uncounted Russian soldiers, and the war is simmering with one Ukrainian soldier being killed every third day or so. In parallel, Russia has gradually reduced Ukrainian access to the Sea of Azov and its two important commercial ports.

Map of the War in Donbass, a conflict in Eastern Ukraine. It shows areas of fighting, and which sides have de facto control of particular regions. Map from Wikipedia.

The current crisis, however, started with Russia’s big military exercise Zapad (West) 21. Russia carries out such an exercise every fourth year, but this was particularly large and focused on Ukraine with about 100,000 Russian soldiers along its borders. Nothing happened then, but the substantial military equipment was largely left in place.

On July 12, Putin elaborated further on his favorite topic with a 5,000-word long article about the ”historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians.” This article was quite ambitious and read like a preparation to declare war on Ukraine. Putin insisted on calling Ukraine ”Malorossiya”, Little Russia. He claimed that Russians, little Russians (Ukrainians), and Belorussians (white Russians) spoke the old Russian language and belonged to one orthodox religion until the 15th century. In great detail, but in a highly selective and distorted fashion, Putin discusses Ukraine’s history. His key accusation is that the nasty West (unclear who) pursues the “Project ‘anti-Russia’, which millions of inhabitants of Ukraine have refuted.” Still, Putin alleged that “Russia is open for dialogue with Ukraine and ready to discuss even the most complex questions. But we have to understand that the partner insists on its own national interest and does not serve foreign interests,” which precluded any discussion with the actual Ukrainian government.

Putin’s underling Dmitri Medvedev followed up with an even cruder article in October. In November, Russian military were amassed around Ukraine once again, but this time not because of any military exercise. This was a blatant military threat to Ukraine. In mid-December, the Kremlin passed on its demands to the United States and NATO. Undiplomatically, these demands were published on December 17. They were very far-reaching.

The Kremlin demanded not only that there would be no more enlargement of NATO, but that the whole enlargement since 1997 should be nullified. The edge was directed against the United States and Ukraine. The United States was asked to guarantee that it would “not establish military bases in the territory of the States of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics” that are not NATO members or “use their infrastructure for any military activities or develop bilateral military cooperation with them.” The eight articles proposed were supposed to be legally binding but all of them were obviously unacceptable to the United States or NATO.

On the evening of Friday, December 17, the Russian Security Council held a meeting. It was untypical in two regards. All its thirteen members attended, and no agenda was publicized. For both reasons, it looked like a preparation for war.

The Kremlin hammered on with its war agitation, and on December 21 a major escalation occurred, when Putin appeared before the collegium of the Russian Ministry of Defense. As usual, Putin blamed the U.S. for rising tensions in Europe. He stated that the United States and its allies “must understand that we have nowhere further to retreat” and that Russia could not allow them to deploy missiles in Ukraine that would be a few minutes’ strike

distance from Moscow. “Do they really think we’ll sit idly as they create threats against us?” While Putin insisted that he was not issuing an ultimatum, he effectively did, stating that

Russia will “take adequate military-technical response measures and react harshly to unfriendly steps” by NATO, without further elaboration.

Making the matter worse, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu spoke after Putin. He claimed that his ministry had established “the presence of more than 120 representatives of private U.S. military contractors in the towns of Avdeyevka and Priazovsk in Donetsk oblast.” “In order to carry out provocations in the towns Avdeyevka and Krasny Liman they had delivered unidentified chemical components.” What Shoigu told us was effectively that he was preparing a provocation to start a war with Ukraine, as Hitler did in Gleiwitz and Stalin in Mainila. Nobody has reported any American contractors in Donetsk oblast and the OSCE has 700 observers there.

The meeting at the defense ministry was followed by a late evening video meeting with the Security Council starting at 9 pm. Only Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov was missing. Indeed, this is no time for diplomacy. Russia’s television propaganda is hitting hard. Everything suggests that Putin is really opting for war.

Why is Russia so Aggressive Now?

As is usually the case with Russian foreign policy, the Kremlin has many objectives. It wants Germany to certify its gas pipeline Nord Stream 2 as fast as possible; break up the European Union market regime for gas and return to Soviet-style long-term contracts with gas prices tied to oil; weaken Ukraine and Moldova; force Moldova to abandon its European Association Agreement and join Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union. Traditionally, Moscow has wanted to break Europe away from the United States. Now, however, it appears to aspire to break the United States away from Europe. Besides, the Kremlin always wants to weaken and split the EU. What Putin wants most of all is a Yalta II, another agreement with the United States about Eastern Europe over the heads of not only East Europeans but of all Europeans.

Putin has many reasons to act now. His popularity and trustworthiness ratings are lower than ever even according to the official Russian polls, while it rose sky-high during his war in Georgia in 2008 and his annexation of Crimea in 2014. Russia’s economy has been stagnant since the West imposed its sanctions over Ukraine in 2014, and it is not likely to grow much. For Putin this means that his relative military might can only decline. He needs to act while he still can. Declining powers often start wars. Remember that Austria-Hungary started World War I by declaring war on Serbia.

At the same time, the West looks weak and disorganized. The United States has a new administration and only one quarter of the 800 top officials have so far been confirmed by the restive Senate. Germany has a new government, which is likely to take a much tougher position on Russia, and France will have presidential elections in the spring. The new US administration has taken greater interest in Ukraine than has been the case since President Bill Clinton in the 1990s. Biden has received President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in Washington this year and three US cabinet ministers have visited Kyiv. The Ukrainian defense forces are stronger than ever, and the United States is providing it with ever more effective support.

Moscow tends to operate with trial balloons. It checks what it can get away with before hitting hard if it finds a good opportunity. Therefore, the collective West – that is, the United States, the EU, and the United Kingdom – need to act jointly, hard and fast. As Keir Giles of London’s Chatham House writes, the West must recognize “that confrontation with Russia cannot be avoided because it is already happening.” He continues “that Russia respects strength and despises compromise and accommodation.” The worst provocation against Russian aggression is not to react or to react too slowly and softly.

If Putin actually attacks Ukraine, he is likely to lose power in Russia. A war with Ukraine would not be popular among Russians, but he could cause tremendous damage before he loses, just like Hitler and Stalin. The greater risk is that the inexperienced and far from complete US administration gives Putin far too much for no good reason, which will just provoke him to further aggression.

Nothing provokes Putin more than weakness.

The United States Remains Pivotal

The role of the United States in this drama is rather confusing. No US president has known Ukraine or Russia as well as Joe Biden. As vice president, he visited Ukraine no less than six times, and he showed that he understood the country very well. Since he became president, the United States has stood up firmly in defense of Ukraine against Russian military mobilization both in April and now. President Volodymyr Zelensky’s visit to the White House on September 1 was a watershed moment. No less than three US cabinet secretaries have visited Ukraine this year (State, Energy and Defense). The key Ukrainian ministers dealing with Washington are naturally Defense Minister Oleksiy Reznikov and Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba, arguably the most respected members of the current Ukrainian government.

On November 10, the United States hosted a large Ukrainian delegation in its new bilateral Strategic Partnership Commission, when a surprisingly strong U.S.-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership was adopted. In particular, the “United States supports Ukraine’s right to decide its own future foreign policy course free from outside interference, including with respect to Ukraine’s aspirations to join NATO.”

On the other hand, a spectacular mistake by the Biden administration on Russia was that it not only waived the legislated sanctions on Nord Stream 2, but even agreed on a German-US Statement on July 21 effectively to protect it, although both parties promised sanctions if Russia used energy as a weapon: “The United States and Germany are united in their determination to hold Russia to account for its aggression and malign activities by imposing costs via sanctions and other tools.” Russia has done so, but the United States and Germany have done nothing. They need to comply with their commitment as fast as possible unless they are to provoke Putin to a war.

Thanks to Putin’s renewed military buildup, he managed to extract another meeting with Biden, a video call on December 7. It was a scary moment. Would Biden stand up to Putin as he has done before, or would he follow the appeasement ideas that have been floated by the Putin apologists here in Washington that seem to have found support in the all-dominant National Security Council (though not much in the State Department and in the Pentagon)?

The immediate aftermath of the video call on December 7 brought relief. Uncharacteristically, the White House immediately delivered a brief but hard-hitting readout, while the Kremlin needed almost three hours to say something. The United States wanted Russia to stay out of Ukraine, while both wanted to have some future talks.

To reiterate, Putin’s greatest aim is a Yalta II and to split the United States from Europe. Sadly, Biden suggested bilateral Russian-US negotiations and then called the leaders of the Western European countries France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom. Eventually, Ukraine and the Eastern European Bucharest Nine managed to get in on the act, but why is the White House giving Putin what he wants?

The United States has already delivered threats of substantial financial and personal sanctions against Putin and his ilk, if he dares to attack Ukraine in an overt or hybrid fashion. These threats must be credible, but are they? One of the most important tasks now for the European Union is to be as firm as the US and thereby make the message to Putin clear, credible and deterring.

What the West Should Do

Rather than focusing on Putin’s aggressive demands, Biden, Ukraine and the West should hammer home their own justified demands on Putin, which are based on international law.

First, Putin should withdraw his offensive forces from Ukraine’s border, Crimea and Donbas. The Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) used to have a sound system of transparency and preannouncement of military exercises of a significant size. Why has the West let up on those standards? It is time to demand their restoration. The European Union should be at the forefront demanding Putin to Ukraine’s sovereignty and the European security order. There must be no “business as usual” if Putin doesn’t accept what is widely considered business as usual, namely obeying international law and agreements and showing Russia’s neighbors and Europe as a whole respect.

Second, the West needs to loudly insist that Russia is the main source of destabilization in the former Soviet Union. The West must persistently demand that Russia withdraws its occupation troops from Donbas, Transnistria, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Russia has repeatedly made international agreements that it will not violate national borders. The West needs to persistently repeat what Russia has committed itself to. It has done so in many forms.

Third, the key Soviet demand in the original Helsinki Final Act of 1975 was that the existing borders in Europe should be recognized. “The participating States regard as inviolable all one another’s frontiers as well as the frontiers of all States in Europe and therefore they will refrain now and in the future from assaulting these frontiers. Accordingly, they will also refrain from any demand for, or act of, seizure and usurpation of part or all of the territory of any participating State.” As the successor of the USSR, Russia has never revoked this legal commitment.

When the Soviet Union was dissolved in December 1991, the peaceful Russian President Boris Yeltsin guaranteed the existing borders between all the twelve remaining former Soviet republics. (The Baltic countries had already left in August 1991.) In addition, in 1997 Russia and Ukraine concluded a bilateral Treaty on Friendship, Cooperation and Partnership. Its key Article 2 states “In accord with provisions of the UN Charter and the obligations of the Final Act on Security and Cooperation in Europe, the High Contracting Parties shall respect each other′s territorial integrity and reaffirm the inviolability of the borders existing between them.” In 2014, Russia violated this treaty, which it revoked after the fact. Needless to say, Putin’s Kremlin is no friend of Ukraine.

Fourth, Russia has made so many international commitments that it regularly violates, not only about borders, but also about human rights. In November 1990, the OSCE adopted the Charter of Paris for a New Europe. It is probably the finest document that Europe has ever embraced. The many signatures committed “to build, consolidate and strengthen democracy as the only system of government of our nations” as well as human rights and the rule of law. Russia has never revoked this commitment that it inherited from the Soviet Union, and it should always be reminded about it.

Yet, at present the finest Russian human rights organization Memorial claims there are at least 410 political prisoners in Russia. Consequently, Memorial has been labeled a “foreign agent,” which, as Russian Nobel Peace Prize laureate Dmitri Muratov so rightly pointed out, really means “enemy of the people.” Alexei Navalny, Russia’s greatest present hero, has delivered a list of 35 top Russian collaborators who should be sanctioned. The United States, the EU and the UK should do so systematically until Navalny is released. It would also be a good idea for Russia to stop the torturing of imprisoned Ukrainians in Russian-occupied Donbas. That would take care of Putin’s call for better human rights in Ukraine.

Instead of revoking its many eminent commitments within the OSCE before Putin, Russia has tried to undermine the OSCE and render it ineffective in recent years. The latest example is Putin’s demand for bilateral negotiations on European security with the United States. European leaders and President Biden should tell Putin that the OSCE was created for such discussions and refuse to accept any new bilateral forum.

The ultimate question to the United States and European Union is: Why talk to a party who has developed lies into their modus vivendi and violates just about every international agreement that it has concluded? No word stated by Putin is worth the paper it is written upon. Frankly, the only relevant response is to swiftly deliver more arms to Ukraine to reinforce its defenses to reduce the probability of a Russian attack. A strong Ukrainian defense is the best peacemaking measure.

What Should Sweden Do?

The current deterioration of the security situation in Europe because of Russian aggression underlines once again our long-standing view that Sweden together with Finland should join NATO. Ideally, this should have been done in 2014, when it was made clear that neutrality on defence for Ukraine provided Putin with the window of opportunity that he sought. Without that ambivalence, Sweden and other European nations would have been better prepared today.

Yet, better late than never. Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova were all neutral when Russian troops attacked them. Neutrality is not possible in the neighborhood of Putin’s Russia. We need to learn from our Baltic neighbors. Their security is a function of their membership in NATO and nothing else. And Sweden and Finland would naturally take this step together.

In January 2020, Folk och Försvar devoted its annual security conference in Sälen to the threat from Russia. It was impressive how broad the consensus was between all the political parties and the non-governmental organizations: everyone desired substantially increased military expenditures. Today, we need to speed this process up and adjust the Swedish defense to the new circumstances. It can no longer be seen as enough to have the ambition for to return to the levels of defense spending of 2005, which already at that time was too low. A lot of things have happened since then, to put it mildly.

One of the best measures undertaken by our current Defense Minister Peter Hultquist is the close strategic relationship he has pursued with the United States, in parallel with Finland’s similar efforts. This is good, but not enough. We need to maintain a good relationship with the US, but we should nevertheless move ahead to a full-fledged membership of NATO. Our strategic relationship with the United States leaves us outside of the NATO discussions, not to mention their decision making.

Sweden’s soft strategic spot is Gotland. It was a clear mistake that Sweden withdrew its military presence from the island and thereby exposed part of Swedish territory. Fortunately, military presence has been restored, but it needs to be reinforced. The Russian Admiral Pavel Nakhimov, who annihilated the Ottoman navy at the battle in the Sinope in 1853 during the Crimean War, coined the phrase “Who controls Sevastopol controls the Black Sea”. The same could be said about Gotland and the Baltic Sea. Sweden has not been to war since 1814. We need to prepare ourselves for much more unstable times.

This means we need an air defense and a navy that are up to the challenges we face in reality, not only in the theories of war games. Today, the Baltic Sea region is filled with tensions. We need to have a preparedness that can deter aggressions, and we need an army that can project force all over the Swedish territory making it clear to Russia that there are no windows open. We also need to make it clear to all our neighbors that we contribute to stability, not instability. Sweden needs to be a contributor to stability by the strength of our defense and by our commitments to our friends in the European Union and NATO.

In sum, the EU and the US must forcefully deter further Russian aggression in order to set the development in Europe onto a path where talks, cooperation and economic development can be possible for all.

Gunnar Hökmark, President of Stockholm Freeworld Forum

Anders Åslund, Senior fellow.